Helping Honey: The Logistics of Saving Bees

Everyone needs food. When getting it is as simple as a short drive down to the supermarket, it’s easy to forget that starvation is a very real problem in the world, and it won’t take much to bring it to our doorstep. Enter bees. With their integral role in agriculture, we need to take an active role in their survival, because it is inextricably tied to ours.

The value of the honey bee to agriculture can’t be overstated. According to the USDA, “One mouthful in three of the foods you eat directly or indirectly depends on pollination by honey bees. The value of honey bee pollination to U.S. agriculture is more than $14 billion annually, according to a Cornell University study. Crops from nuts to vegetables and as diverse as alfalfa, apple, cantaloupe, cranberry, pumpkin, and sunflower all require pollination by honey bees.”

When so much of our food is reliant on one little creature, we have to take great care to make sure that our environmental practices don’t harm them. It’s estimated that in the next six months, 20 million people are in danger of starvation. Since there is already a huge problem with world hunger, we definitely don’t want to be trending the wrong way when it comes to bees.

With the threats of climate change and mass migration looming, we are nearing the precipice of a serious falling-off point for humanity. The wake-up call is going to come one way or another, and right now we have the choice to prepare or be caught off-guard. If we don’t take action now, the world as we know it will change drastically — and not for the better.

In the agriculture industry, sustainable and organic farming practices are at the forefront of research and development, and for good reason. While there are myriad benefits to wholesome farming, our flying, fuzzy friends might need it even sooner than we do. Bees face daily threats, from pesticides that destroy nervous systems to the destruction of their habitats, and it’s on us to recognize and put a stop to the damage. Simply put, if the bees go, so do we.

All Pests Aside

While there are lots of things keeping beekeepers up at night, an issue at the forefront of the discussion is pesticides. The offending chemicals are known as neonicotinoids, a synthetic form of nicotine. Farmers like them because they’re applied as seed coatings, and are incorporated over time throughout the entirety of the plant, eliminating the need for multiple spray runs over a field.

They operate by attacking the nervous systems of pests and have been proven to increase corn yields around 17 percent more than other pesticides, which has led to their widespread use. They represent around 30 percent of the global pesticide market with more than $2.6 billion in sales.

It’s certainly effective, but evidence suggests that they might do their jobs a little too well. Some studies have shown that much of these pesticides are not absorbed by the plants, and instead leach into the soil and groundwater. It makes its way into the environment, where it can adversely affect other insects, and even birds.

Image source: Tony Linka Illustration

The study that brought this issue into the public eye was one conducted by Harvard professor Chensheng Lu. In the study, he took two groups of bees and exposed one to neonicotinoid pesticides. The other was a control group. The colonies exposed to the chemicals experienced something called “CCD” or “Colony Collapse Disorder,” where bees with damaged nervous systems do not return to their hives, leaving them empty.

It’s not all cut and dry, though, as the methods behind the study have since received some substantial criticism regarding its small sample size and questionable pesticide dosage. Some bee experts and researchers say that 12 colonies isn’t nearly enough to obtain reliable data, and that the amount of pesticide administered was up to 100 times more than bees would actually experience in the wild. They say it’s more likely that declining bee populations are being caused by pathogens like parasitic mites that feed on bees’ bodily fluids, among other threats like climate change.

Right now it’s hard to tell exactly what is menacing our pollinators, and the most likely answer is that there’s no single issue that is causing the entire problem. More research will have to be done — but that doesn’t mean there aren’t real solutions that can help them. One thing is clear, and it’s that we have to examine the logistics of how we raise bees and protect our crops.

The work begins on our nation’s farms.

Stress Management

One thing we have in common with the humble honey bee is stress. The commercial bee farming industry transports large quantities of honey bees all over the country to pollinate seasonal crops, and it appears to have a negative effect on their health.

The stress caused by being moved long distances has been shown to result in underdeveloped food glands and a higher susceptibility to fungal infections. Large numbers of bees contained in one place allows pathogens to spread quickly, and the fact that they’re usually pollinating an area with only one kind of plant means that the colonies are overall less healthy.

Image source: New Organics

Conversely, organic farming practices have been shown to improve colony health drastically. Typical organic farming attempts to reduce or eliminate the use of chemicals, opting instead to use organic pest management techniques. It also fosters a more natural environment for them to live in, with higher biodiversity as opposed to the homogenous environments provided by industrial farms. This leads to happier, healthier bees that don’t have to deal with the experience of perpetually being packed away en masse and transported to faraway, artificial environments.

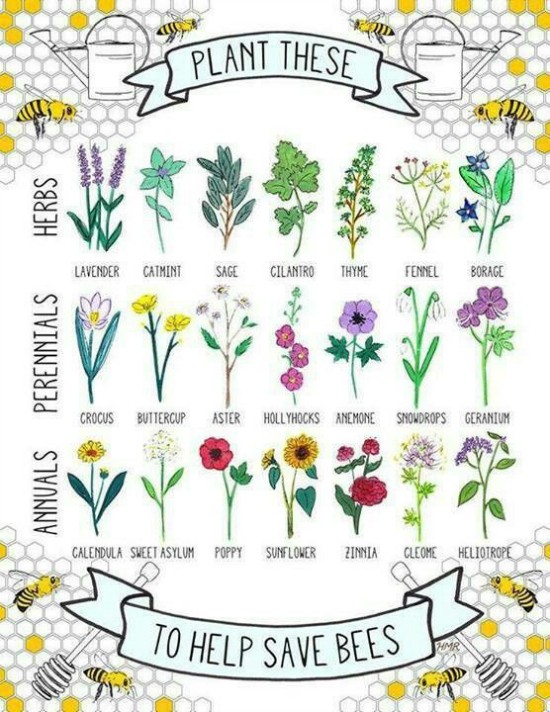

A great method for farmers to avoid using industrial bees is for them to simply plant bee-friendly plants nearby. This will draw pollinators naturally, and eventually those plants will multiply and bring more. It’s a cycle that simply needs farmers to kickstart it.

Another, more subtle, benefit of creating your own bee-friendly environment is that the bees that are attracted to it are domestic. Most of the bees used in the industry today are actually non-native species, brought over from foreign suppliers. As our bee issue becomes more widely known, a tempting solution is simply to import large quantities of them.

However, these bees have been found to harbor alarming numbers of parasites and other pathogens, possibly causing more harm than good to our native species. While the result may not be as immediate, it’s safer and more beneficial to plant their favorite flowers and let them gravitate to our crops naturally.

The Personal Touch

But what if you’re not a farmer? You might not be able to do things that have an impact on the level of large farms and pesticide producers, but you can still lend a hand from wherever you live.

There are countless useful and fun DIY projects that can help us get the business of bees back on track. The first, most obvious one, is to grow your own bee garden. There are all kinds of guides and resources describing which plants to buy and how to grow them.

While many people may be averse to drawing hordes of bees to their house, they can take solace in the fact that honey bees are very docile and rarely sting. Not only will you have a garden of beautiful flowers, but the bees you draw will help all the plants near you multiply and thrive.

Image source: Moral Fibres

Another way to fight for the bees is with your wallet. Buying raw and locally produced honey from smaller, organic farms can ensure that you’re aware of not only where it’s coming from, but how it’s being produced. It also sends a message to beekeepers and honey producers, and if enough consumers choose more conscious honey, we can create a shift toward more sustainable, healthy colonies, and less industrial monocultures that eventually take their toll on bees.

Even buying organic produce in general is helpful. As organic farms avoid pesticides, they’re improving biodiversity in their area regardless of whether they actually raise bees or not. While it’s important to note there’s no such thing as truly organic honey, pollinating organic produce is much healthier for bees than pollinating pesticide-coated ones. If people spraying pesticides on produce must wear hazmat suits, I can’t imagine that being any good for our fuzzy friends.

Whether you’re a farmer, a homeowner, or a college student, there’s always a way for you to pitch in and help the bees in their hour of need. From research on safer agricultural chemicals to growing bee-friendly plants in your backyard, almost everyone has the opportunity to do something.

Since no one will be immune from food scarcity forever, we will all feel the effects of this problem eventually. This is why it’s important for us to all lend a hand and do what we can to make sure that the way we farm, and the way we live, is conducive to the survival of these little bugs that hold so much of our food supply in their small, fuzzy hands… legs? You get the picture.